The significance of Turkish ceramic tiles occupies a prominent place in the history of Islamic art. Its deeply enriched heritage, which can be traced as far back as the Uighurs of the 8th and 9th centuries, owes its subsequent development to Karakhanid, Ghaznavid, and Iranian Seljuk art.

|

| Throne scene on a star-shaped tile using the Iranian-Seljuk minai technique. Aladdin Palace, Konya, Turkey. Image via www.turkishculture.org. |

|

Siren on a star-shaped tile, underglaze painting, Kubadabad Palace, c. 1236. Karatay Madrasah Museum, Konya, Turkey. Image via www.turkishculture.org. |

Countries with colorful histories, such as Turkey with its sovereign past that includes the Byzantine and Ottoman empires, have always provided a deep-rooted fascination to outsiders because of their culture, traditions, food, and most importantly, the art produced within the country. It’s through this art that we, the current generation, are allowed to take a brief glimpse through the artisans mind and eyes of what was seen, felt, and experienced at the time.

|

| Sphinx on a star-shaped tile using the luster technique. Kubadabad Palace, c. 1236. Karatay Madrasah Museum, Konya, Turkey. Image via www.turkishculture.org. |

Turkish Ceramic Tile Develops

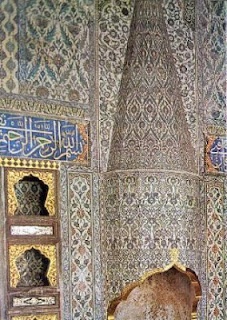

When the Seljuks (Turkic nomads from Turkmenistan who were related to the Uighurs) victoriously conquered the Byzantines at Malazgrit in the early part of the 11th century, they brought with them their knowledge and talent for creating works of art on ceramic materials. As a result, a distinctive style of Seljuk art and architecture emerged by the 13th century. Seljuk mosques, medreses (a building or group of buildings used for teaching Islamic theology), tombs, and palaces were lavishly decorated with these exquisite, handmade tiles vividly in turquoise, cobalt blue, eggplant, and black.

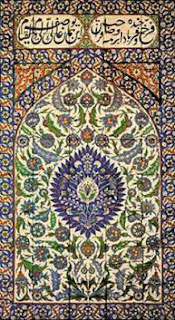

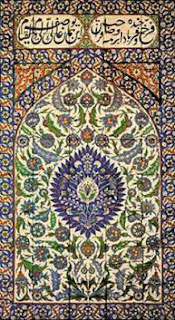

By the late 15th and early 16th centuries, a new period in Ottoman tile and ceramic-making had emerged in Iznik. Artisans employed in the studios of the Ottoman court were sent to Iznik so their designs could be interpreted upon the ceramic wares and tiles that would adorn the palaces. As a result of the patronage, Iznik was known as the most artistically and technically advanced ceramic region.

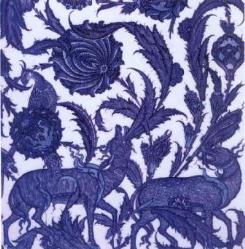

Early on, the Iznik style of ceramic artwork became distinctive with its blue and white designs and motifs of foliage, Arabesque patterns, and Chinese clouds. Court-appointed artisans were now imitating the 15th century Chinese Ming porcelains that had begun to permeate the Ottoman court.

By the middle of the 16th century, natural motifs such as plants, flowers, ships, animals, and even people, began to appear on ceramic tile. With their wide variety of vivid colors, the demand for ceramic tile as decorations surged with the extensive building programs undertaken by Suleiman I (1520-1566) and his successors. Countless examples of mosques and tombs across the Ottoman Empire were adorned with the products of the Iznik potters' skill.

Turkish Tile-Making Techniques

During the Anatolian Seljuk period, architectural decoration involved the use of glazed and unglazed bricks were used to produce a variety of patterns on the façades of buildings. The most frequently color used for the glaze was turquoise, followed by cobalt blue, eggplant violet, and sometimes black. Hexagonal, triangular, square, and rectangular monochrome tiles were also used in creating architectural details.

However, unlike brick, these geometric shapes were used for indoor applications. The geometric tiles, made from a hard, yellowish paste, were glazed with vibrant hues of turquoise, cobalt blue, violet, and occasionally, green. There are also rare examples of these geometric tiles in existence that possess traces of gilding.

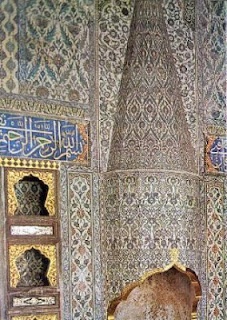

Further, the Anatolian Seljuks also incorporated extensive use of mosaic tile art for the interiors of domes, transitions to domes, vaults, mihrab niches, and walls.

Unfortunately, by the 18th century, the ceramic industry in Iznik had died out completely and another city, Kutahya, replaced it as the leading ceramic arts center in western Anatolia. Kutahya succeeded where Iznik failed in its ability to keep up with orders while maintain their renown product integrity. However, during the first half of the 19th century, Kutahya's ceramics industry also suffered a downturn.

|

| Polychrome tiles, underglaze painting, harem of the Topkapi Sarayi, Istanbul, 16th century. Image via www.turkishculture.org. |

Lastly, there is a widely held belief that figurative painting in Islamic art is prohibited, in accordance with the Koran. According to Turkish Culture, “Religious rulings issued only in the 9th century discouraged the representation of any living beings capable of movement, but they were not rigidly enforced until the 15th century. Figural art is especially rich in tiles, as well as stone and stucco reliefs of the Seljuk period, adorning both secular and religious relief monuments. The subjects included nobility as well as servants, hunters and hunting animals, trees, birds, sphinxes, lions, sirens, dragons and double-headed eagles.”

|

| The tiled hearth of the crown prince’s apartment in Topkapi Place, Istanbul, Turkey. Image via www.turkishculture.org. |

How would you use Iznik-patterned tiles that are still produced today? Have you been to Turkey to see any of the above-pictured pieces?

No comments:

Post a Comment